02.10.2025

Reds with deep state connections

Tobias Abse reviews John Foot The Red Brigades: the terrorists who brought Italy to its knees Bloomsbury, 2025, pp450, £25

John Foot’s lengthy book is the first English-language general account of this Italian leftwing terrorist group to be published for some decades. It includes a large number of relevant photographs extracted from a number of archives.

The book traces the development of the Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades) from their foundation in 1970 until the murder of Roberto Ruffilli in April 1988, which Foot regards as the last killing by the BR proper - choosing, probably rightly, to make no mention of subsequent sporadic violent activities by those seeking to revive the organisation (eg, the killing of Marco Biagi in Bologna in 2002), apart from in an endnote (p397). Chapter 1, ‘The world that made the Red Brigades: Italy, 1968-1974’, makes some attempt to sketch the background to the group’s founding, placing an emphasis on the influence of the Uruguayan Tupamoros that some might see as excessive.

The Red Brigades is largely based on a wide variety of predominantly Italian-language secondary literature, although it often quotes contemporary newspaper accounts of the incidents it covers in detail. As a professional historian, Foot is well aware that some might possibly feel he could have made more use of primary sources (archival and oral) in the way he has in some of his other books. As he points out, “much of the primary material remains difficult to access” (p398) - he complains about a two-year wait to get permission to see some material relating to BR trials in the Turin State Archive, and about the fact that he was not allowed to photograph it or take notes.1

Foot chose not to attempt any interviews with the surviving BR leaders - “they have said what they want to say” (p395). Of the three he mentions by name – “Curcio, Moretti, Franceschini above all” (p394) - the last has died since Foot published the book. In my view, not Foot’s, who seems more hostile to Franceschini than to the other two, he was the only one who might perhaps have been willing to say something more, precisely because he did not in later years subscribe to the official version of the BR’s history - the one endorsed by the Italian state, as well as Curcio and Moretti, although it was largely concocted by a lesser former BR terrorist, Valerio Morucci, soon after his arrest.

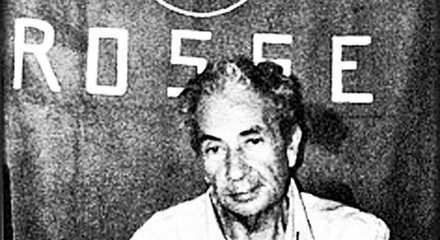

The one episode that made the BR internationally notorious is, of course, the kidnapping and murder of the Italian Christian Democrat leader and former prime minister, Aldo Moro, in 1978. Without the enduring memory of this central event, it is unlikely that anybody would have suggested to Foot (who has not previously specialised in writing about Italian terrorism or the Italian far left - preferring topics like the Italian football, cycling or radical psychiatry) that he write a book about the BR that is very clearly aimed at a general readership rather than a purely academic niche market.

Unfortunately, his coverage of the Moro affair (chapters 13 and 14) is the weakest section of the book. What we are offered is the official version, in which an extremely efficient band of terrorists captured Moro without much difficulty after rapidly killing his driver and four bodyguards, and then held him in the middle of Rome for 55 days without anybody having the remotest idea where he was until he was found dead in the boot of a car on May 9 1978.

These days, this account is more difficult to defend than it was at the time, when the American historian, Richard Drake, took on the academic defence of the official version in The Aldo Moro murder case (Cambridge MA 1995)2. Here we have Foot at his most polemical. There is not enough space in a review to cite all his vicious attacks on those who cast any doubt on the official version,3 so I will quote a sample passage:

… a near obsession with the minor details of the Moro kidnap and murder has developed over nearly 50 years - dominating the history of the Red Brigades and obscuring numerous stories and tragedies linked to other victims. Moro has overshadowed everything and the minutiae of the precise quantity of bullets, the exact number of brigatisti, the escape route, the cars, the bases, the “people’s prison” - have been worked over again and again by journalists, politicians, parliamentary commissions, documentaries, novelists, historians. The endless search for some sort of outside influence on the BR - the puppet masters - was also linked to a powerful set of stereotypes - about Italian inefficiency, or Italian goodness (pp240-41).

This is not the only occasion on which Foot uses the phrase, “puppet masters”. He is obviously referring to a book that is totally absent from his bibliography and from all his hundreds of endnotes: P Willan Puppet masters: the political uses of terrorism in Italy (London 1991).4 Foot may not agree with, or approve of, Willan’s work, but not to refer to it is intellectually dishonest, as in my view is much of chapters 13 and 14.

These chapters make absolutely no mention of the Masonic P2 Lodge, or the extent to which P2 had infiltrated the Italian secret services, police and Carabinieri military force - which might explain why the state’s efforts to find Moro in 1978 were so ham-fisted, to put it mildly. It should be added that the only reference to P2 in the entire book is one paragraph (pp327-28), suggesting it was “involved obliquely in political violence, particularly the ‘strategy of tension’” (p328).

This minimalisation of P2’s role in financing and organising neo-fascist bombings - there was nothing ‘oblique’ about Licio Gelli’s financing of the Bologna bombers - is followed by another unpleasant rant about “many conspiracy theories relating to Italian politics and history in the 1970s and 1980s”. Needless to say, there is not a single reference to P2 leader Licio Gelli anywhere in the book. Perhaps we should be grateful that we are spared any claim that the Bologna bombing of August 1980 was organised by Palestinians - the standard claim of Gelli’s Italian apologists in the far-right Fratelli d’Italia.

The absence of Gelli’s name anywhere in Foot’s text is symptomatic of a wider pattern of denial. There is an equally deafening silence about the role of Steve Pieczenik, the sinister American advisor to Interior Minister Francesco Cossiga during the Moro affair. Even if Foot has not read the book by Emmanuel Amara, Abbiamo ucciso Aldo Moro (‘We killed Aldo Moro’),5 in which Pieczenik himself admits that he and Cossiga decided to let Moro be killed, Pieczenik’s frequently appears in other books about the Moro affair.

In other words, it is not just a question of vague ‘conspiracy theories’ about American involvement, but repeated references to a specific individual, who has always refused to testify in Italian courts or parliamentary commissions dealing with the Moro affair. Of course, the significant silences about Gelli and Pieczenik are matched by the absence of any mention of Corrado Simioni, even to refute Franceschini’s theory about Simioni’s role as an external influence on the BR during Moretti’s leadership, particularly during the Moro affair.6

The trouble with Foot’s generic attack on ‘conspiracy theories’ is the only such work that he bothers to refer to in any detail is the Fasanella and Rocca book about the alleged role of the conductor and composer, Igor Markevitch, as a mysterious intermediary during the last days of Moro’s life7 - a work full of nonsense about Rosicrucians, the Knights of Malta and, in a rather coded way, ‘the world Jewish conspiracy’.

Foot gives a detailed account of the BR kidnapping of the corrupt Neapolitan politician, Ciro Cirillo, in 1981 (pp335-44), in which the Christian Democratic Party ended up paying a huge ransom, and Cirillo emerged alive, even if utterly politically discredited. The contrast with the DC’s behaviour during Moro’s captivity should be obvious. As Giovanni Moro, Aldo’s son, said to La Repubblica on September 5 2003, “It is a fact that in that case - and only in that case - the Italian state decided neither to negotiate with the terrorists nor seriously attempt to free the prisoner”.8 Foot’s comment about the Cirillo case (“the context - involving the BR, the DC, the secret services and the Camorra - was astonishing”) is in my view rather absurd, but regarding it as “astonishing” is a necessary corollary of taking the official version of the Moro affair at face value.

Whilst Foot offers what is in general a well-written, detailed and frequently very graphic account of the BR’s principal actions, where I (and many others) would differ from him is over his contention that the BR’s success - in their own terms - as a terrorist group was due to the rigid internal rules they adopted in 1974, discussed in chapter 6, and the intensity of their group loyalty - at least until Patrizio Peci became a pentito (supergrass) in 1980 (see chapter 17).

My own view is that their survival after 1974 was due to the fact that their original leadership was replaced by first Mario Moretti and then Giovanni Senzani - both of whom were in some way connected to Italian or foreign secret services. The case against Moretti was best made by Sergio Flamigni in La sfinge delle Brigate Rosse (Milan 2004), which Foot does refer to once, briefly and very dismissively (pxi). The case against Giovanni Senzani was best made in a much more recent book, of which Foot may perhaps have been unaware.9

The original members of the BR were sincere, if totally misguided, revolutionaries, and the vast majority of subsequent BR rank-and-file members were of the same ilk - infiltration at the top was not replicated on a large scale at the bottom. Moreover, there is no reason to suppose that Barbara Balzerani, the last leader of the BR (or, to be more exact, of one of its fragments), was in any way manipulated by outside forces - the bloodthirsty path she pursued was hers alone.

Foot chose to dedicate his book to Salvatore Porceddu and Salvatore Lanza - two very young low-ranking policemen killed by the BR in Turin in December 1978. Although this murder was one of the BR’s most brutal and pointless actions, it is hard not to be cynical about Foot’s motives for this dedication.

Despite the book’s many literary merits, Foot’s aim in writing it may not have been purely scholarly, or even largely commercial. When attacking “conspiracy theories”, he says that

… one logical outcome of these interpretations is that … thousands of magistrates, judges, lawyers, police officers, carabinieri either had the wool pulled over their eyes or were themselves part of a plot that reached the very top of the state - and even to international organisations, including those in the USA. This is a monstrous suggestion. If it is true, the entire Italian state should be dismantled (pxii).

Beyond remarking that I never thought Paul Foot’s son would go quite so far in defending the Italian state and “international organisations, including those in the USA” (presumably the CIA, Nato and Operation Gladio), I leave it to readers to assess whether it is a “monstrous suggestion” that the Red Brigades, like their contemporaries in the neo-fascist terrorist groups, ended up as pawns in Washington’s game during the cold war.

-

He appears to see no contradiction between these difficulties and the very rose-tinted view of the Italian state apparatus he expounds elsewhere in the text.↩︎

-

Surprisingly, Foot does not quote Drake. However, he is eager to cite the official version’s Italian academic defender - the civil servant, Vladimiro Satta, whose principal work is Odissea nel Caso Moro (Rome 2003).↩︎

-

I discussed the views of doubters - including Moro’s widow, Eleonora, and his son, Giovanni - in my article, ‘The Moro affair: interpretations and consequences’, in S Gundle and L Rinaldi (eds) Assassinations and murder in modern Italy: transformations in society and culture Basingstoke 2007, pp89-100.↩︎

-

It was re-issued by a minor American publisher in 2002. One suspects that any one of the dubious characters named in it took advantage of English libel laws to block any re-issue in the UK.↩︎

-

Rome 2008 (translated from the French original, Nous avons tué Aldo Moro, Paris 2006).↩︎

-

Foot refers to the book in which Franceschini puts this forward, but he does not mention Simioni - in other words, Foot is well aware of the whole ‘Superclan’ story, according to which Simioni manipulated the BR via a much more clandestine organisation of his own.↩︎

-

Chapter 14, endnote 1, p422.↩︎

-

The state did free the prisoners, Vittorio Vallarino Gancia and General James Lee Dozier, in 1975 and 1981 respectively, having used armed force against the BR.↩︎

-

M Altamura Il professore dei Misteri. E con lo Stato e con le BR: Giovanni Senzani e la storia segreta del doppio livello Milan 2019.↩︎